1. Background

Early Settlement in Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego region, located in the extreme south of South America, has been the subject of archaeological studies to understand the early settlement of this inhospitable and fascinating area. Archaeological findings and advances in radiocarbon dating have revealed the existence of a land bridge in the Strait of Magellan, which connected the continent with Tierra del Fuego between 13,000 and 10,000 years BP2 (Before Present) (R. D. McCulloch et al., 2005; R. McCulloch et al., 2009; Ponce et al., 2011).

There is a general consensus among researchers that the initial waves of terrestrial settlement reached the Isla Grande of Tierra del Fuego via the mentioned route in the strait. The earliest radiocarbon dating indicates an approximate age of 10,600 years BP based on samples from the Tres Arroyos site. Another early site, which has provided valuable archaeological evidence, is the Marazzi site, located southeast of present-day Bahía Inútil, dating back to 9590 years BP (Laming-Emperaire et al., 1972; Morello et al., 1999; Salemme et al., 2017). Both sites are representative of the earliest hunter-gatherer human communities that settled in Tierra del Fuego and successfully adapted to the extreme environmental conditions of the area.

However, it was not until 3000 years later that an economy dedicated to the exploitation of marine resources became evident, marking a coastal adaptation in the region (Legoupil et al., 1997; Orquera et al., 2009). To the north of the Magellan Channel, we find sites such as Punta Santa Ana, dating to 6,500 BP, and in the Beagle Channel area or Ona-Ashaga Tunnel I and Imiwaia I, with dates ranging from 6,400 to 4,300 BP (Ortiz-Troncoso, 1978; E. Piana et al., 2012; E. L. Piana et al., 1992; Zangrando, 2009). These archaeological findings provide evidence of a significant shift in the lifestyle of the communities, characterized by the emergence of a prominently maritime economy. This transition led to a heightened reliance on marine resources and a more extensive exploration of coastal regions, leading to the formation of the earliest shell deposits, known as “conchales” or shell midden deposits. These deposits consist of mounds formed by the accumulation of discarded food remnants, primarily marine shells, although they also include waste from other sources such as land and marine animals, as well as plant materials in the form of charcoal or seeds. In certain areas of the Beagle Channel (FIG. 2), these shell deposits are clearly visible in satellite photographs, while in densely forested regions, they may be concealed beneath layers of trees and shrubs.

The landscape of Tierra del Fuego has also undergone significant paleo-ecological transformations over time. Until around 5,800 BP, the region was dominated by steppe. However, from then on, the current Nothofagus forest began to develop, although it would not be until 4,000 BP that this ecosystem would become fully established in the region (C. J. Heusser et al., 1988; Calvin J Heusser, 2003; Rabassa et al., 2000). These changes in the landscape had implications for the human communities that inhabited Tierra del Fuego, generating new resources for human subsistence (Zangrando, 2009). Some authors, such as Orquera and Piana (2009), point out that a maritime adaptation would not have been possible without an ecosystem that provided resources such as wood and bark for canoes or harpoon handles.

2. The passage in today’s Darwin Range

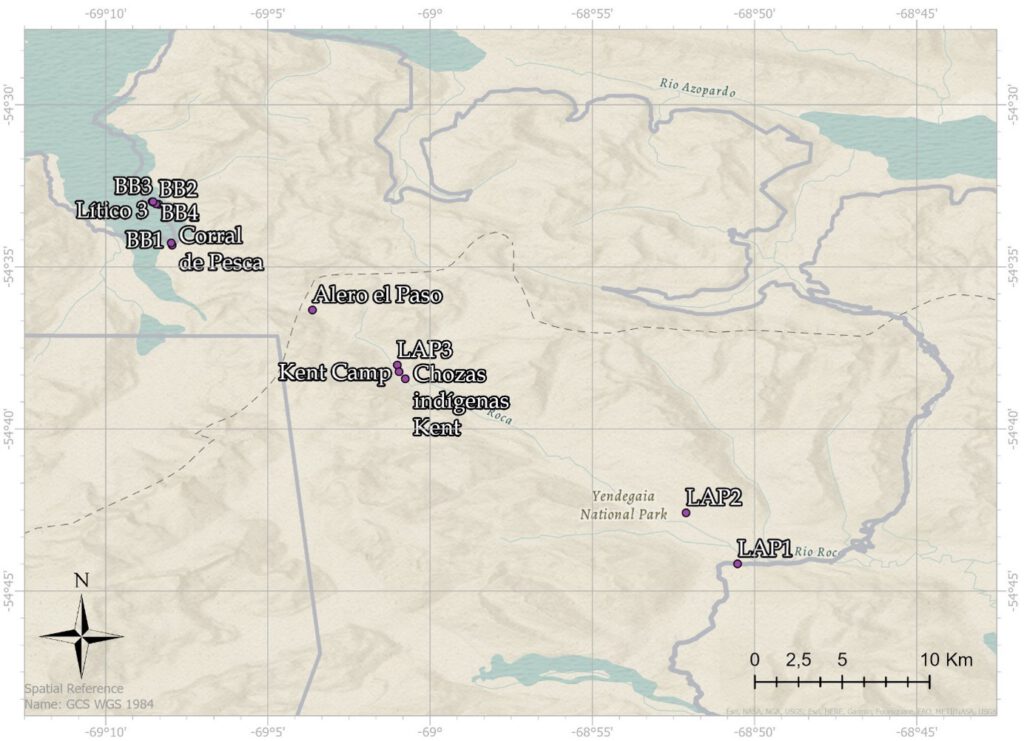

Perhaps one of the key points to understand the mobility of the communities that inhabited the place is the moment in which the glacial ice of the Darwin Mountain Range opens. Based on available evidence, it is likely that this occurred sometime between 8,240-7,260 years BP and possibly as late as 5,800 years BP. Notably, during this timeframe, there is a noticeable rise in Nothofagus pollen levels observed in marine sediment records. This fact is linked to the development of a dense forest in the coastal zone (Ponce et al., 2011). As we have pointed out, in the Ushuaia area there are early records of shell middens, but so far there was little information in the area between Bahía Blanca and Bahía Yendegaia.

We know of the existence of large areas of shells middens and pithouses in the Bahía Yendegaia sector. There is archaeological documentation since the first excavations of Junius Bird and up to the recent publication on the rock paintings of Francisco Gallardo and the excavations in the framework of the road construction (Bird, 1938; Gallardo et al., 2022) (FIG. 2). However, prior to the project there was a documentary void around Caleta María and Bahía Blanca (Prieto et al., 2022). The main hypothesis is that, if it had been a place of passage and connection between groups, it would be expected to find areas of residence and occupation in the form of archaeological sites on both sides of the mountain range and during the long passage that develops in the Lapataia Valley.

The passes, until recently called “Pasos de Indios” (Indian Passage) and nowadays Pasos de Indígenas (Indigenous Passage) correspond to geographically located places that were used as optimal routes to minimize effort (Alfredo Prieto et al., 2000). These passages were habitually used by canoe communities, although not exclusively, and linked distant points of land:

Some points of the archipelagos are accessible by sea at the cost of a long detour, while the crossing of narrow isthmus allows to reach them in a few hours even hoisting the canoe through peaty terrain. Often these isthmuses are at the bottom of ancient glacial valleys, through which were connected in a time when the water level was higher, maritime systems today independent. These lands are occupied by peat bogs and are dotted with lakes.

(Emperaire, 1963:177)

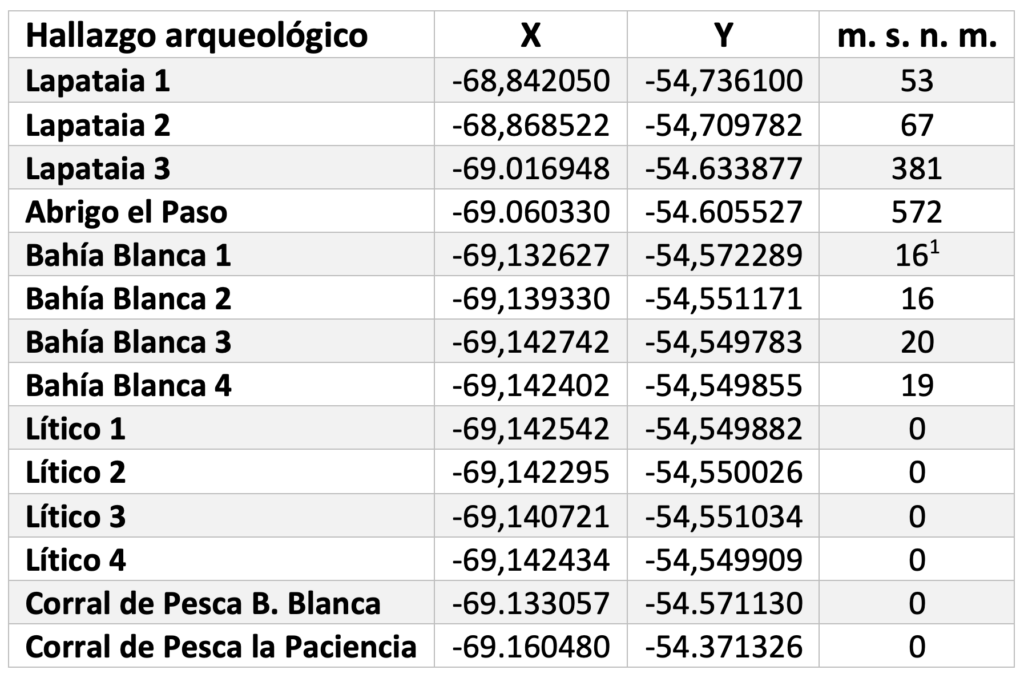

Passes such as the one explored, which joins the area of Admiralty Sound and Beagle Channel, do not seem to be the usual ones, in this case the route consists of several days of walking and the transport of canoes seems unlikely. There are numerous ethnohistoric publications that give an account of the use of the area by the native communities. Some of these are documented by renowned explorers such as Captain Philip Parker King in 1839 (King, 1839) or Captain Luiz Philippe de Saldanha da Gama in 1882 (Saldanha da Gama, 1887). But perhaps the most interesting episode is that given by the search for the Indian Passage between Admiralty Sound and the Beagle Channel that developed from the twentieth century (see Garcia O., 2015). The motivation behind this exploration was driven by factors of exploration, commerce, and strategic interests. Several explorers who embarked on these journeys, such as Otto Nordensjköld (1896), Carl Skottsberg (1908), and Alberto de Agostini (1913), were already aware of previous information regarding the existence of an indigenous passage. In fact, as early as 1885, Thomas Bridges had already identified the use of this passage by the communities arriving at the Ushuaia Mission (SAMS, 1886).

The painter, writer, and explorer Rockwell Kent’s expedition in 1922 was not the first instance of a “white man3” crossing, as he acknowledges. The expedition led by frigate lieutenant Tomás Zurueta in 1892 had already traversed the route between Lapataia and Bahía Blanca (refer to García O., 2015). However, Kent’s writings and drawings hold significant relevance (Kent, 1924):

They reported great difficulties on the way, deep streams, mountains and valleys. These Indians, being unused to land travel, may have exaggerated the difficulties. The remains of Indian shelters that we found would indicate our route as being the one travelled by the Alacaloofs. Our subsequent inquiries confirmed that we were the first white discoverers of the pass.

(Kent, 1924: 120)

Perhaps the most relevant content for archaeology corresponds to an episode of Kent, fruit of chance, or of his good literary rhetoric for the discovery:

Here it came to me that I had left my cap at our last resting place, and I returned to find it. While I was reproaching myself for thus wasting my strength and our time, I was rewarded by the discovery of the decaying frames of two Indian shelters. I was to learn in Ushuaia that in former years, when the English mission at that place was active, there had appeared occasional bands of Indians of the Alacaloof race, who by some unknown and difficult way had come across the mountains from the north. It was undoubtedly their traces that we’d hit upon.

(Kent, 1924:115)

This episode he narrates is very interesting because it documents the undoubted presence of indigenous structures around the pass. This important data and the route he drew were and are relevant to understand the place of passage between Bahía Blanca and Bahía Yendegaia (FIG. 3).

The campaign developed by Terra Ignota in 2021 had already documented evidence of archaeological material in the area near the “Death” or “Kent” Pass. This lithic material was in the Alero, momentarily called El Paso. The fact of making this finding motivated the development of an investigation that would allow documenting both the route of the pass and the possible archaeological findings that could be found.

3.Methodology

The planned and programmed methodological strategy was based on visual archaeological prospection, carried out by a multidisciplinary group and without any impact on cultural heritage. The first stage consisted of an analysis of the ethnohistoric record and intangible heritage. Documentation was carried out based on ethnohistoric sources such as maps, diaries, and travel chronicles. These sources made it possible to characterize the observations of the place made by navigators, travelers, and settlers from the seventeenth century to the mid-twentieth century. During this information gathering process, the toponymy of the place and its origins were also documented.

The visual prospection was carried out by walking, in a non-systematic way, the areas of archaeological interest that were in the established route of exploration of the valley. In each case, information related to the location, natural characteristics of the area, conservation and recording of the findings was documented.

Another aspect of the exploration was the archaeo-historical analysis of the native forest. Evidence of historical use or disturbance of the forest ecosystem was recorded, such as the presence of cultural marks on trees and bark scars on living and dead trees.

The basic structure of the findings log was as follows:

- Description of the site in audio or written format.

- Taking of GPS coordinates using exploration equipment and real-time visualization on the Web Platform, where users could follow the expedition log (https://terra-ignota.net).

- Photographs with scale.

- 3D photogrammetric capture of the most relevant findings using Lidar technology by Florencia Curci and Carsten Stabenow. 3D Lidar is a state-of-the-art technology that allows rapid documentation of objects and locations, saving them in manipulable, geo-referenced files.

- Documentation of soil variables (pH, phosphates, temperature, …) using the Ignota Logger sensor developed by Victor Mazón.

4.Registration of archaeological sites

The archaeological recording based on visual prospection in the interior zone of the passage was carried out by two of the three exploration teams. In each group there was the presence of an archaeologist with the academic degree of PhD. In Group 1, Dr. Alfredo Prieto from the Universidad de Magallanes and, in Group 2, Dr. Robert Carracedo Recasens from the Universidad Austral de Chile. The main motive was to carry out a proper recording of the findings and, at the same time, to transmit academic knowledge and local archaeological heritage to the work teams. The fundamental purpose was to conduct archaeological research involving different actors with diverse visions and motivations (Milek, 2018; Smith, 2014). There is an intrinsic potential in what has been called transdisciplinary archaeology, coupled with the discovery of new sites based on practices that consider the inclusion and participation of different agents. In this case, we had the perspective of members of the Yagán communities by Claudia González, and Selk’nam by Fernanda Olivares and Hema’ny Molina, as well as different sound artists, a geologist, and a philosopher.

Group 1 started in Yendegaia Bay and continued through the Lapataia Valley, following the southwest bank of the Lapataia River. The trail passed through forests, wetlands, and river deposits. Group 2 began its journey at the Lagunas Pass (previously visited by Skotsberg in 1908) and continued along the Condor River Valley until reaching the Lapataia Valley. The east bank and the adjacent forested area were traveled and documented. This road was composed of forests, peatlands, and fluvial deposits in the upper part of the valley. Group 3 was in the Bahía Blanca area, which was of significant interest due to its unexplored nature prior to this study.

Groups 1 and 2 were found on the east bank, in the upper course of the river, when the valley began to become more vertical. From that point on, the east side of the river was documented. The Lapataia River was crossed and traveled along the western sector in what is known as Paso de la Muerte (Death Passage), Paso Kent (Kent Passage) or Paso de Indios (Indian Passage), all exonym names. Both groups documented the Alero del Paso using different techniques detailed in the methodology.

The arrival of Groups 1 and 2 in Bahía Blanca facilitated a meeting with Group 3, leading to the significant archaeological documentation of the coast and forests to the south and west of the Bay. These areas revealed important shell middens and fishing weirs. Ultimately, the entire team was able to exchange experiences and engage in transdisciplinary activities during the Forum held in Caleta María.

The ordering of the findings that are presented below is based on the route taken.

4.1 Lapataia 1

This is an archaeological site4 located in an open Nothofagus forest (FIG. 4), 12.5 km from Roca Lake and 14 km from Yendegaia Bay. This forest is protected from the wind and has abundant fresh water from nearby streams that are tributaries of the Lapataia River. In an approximate area of 250 m2 there are different bone fragments and evidence of lithic carving. These objects can be observed due to the removal of the subsoil caused by cattle. In addition, the presence of a silty organic sediment is noted just below the vegetation layer.

A set of broken guanaco bones, probably used to extract marrow, has been documented at the site. It is possible that there are “crushers”, but due to the state of preservation of the bones, it cannot be clearly ascertained. The presence of at least two individuals has been recorded, since two mandibles and two scapulae of different sizes were found, all with percussion marks. In addition, one of the scapulae has cut marks on the proximal part. A gray flake was also found, made of medium quality raw material, but showing a conchoidal fracture. The most likely hypothesis is that it is a temporary settlement by indigenous communities, perhaps terrestrial, that were entering the valley.

4.2 Lapataia 2

In the area of the middle course of the Lapataia River, an ancient circular grouping of stones was detected (FIG. 6). It is a find located in the flat part of the valley a few meters from the forest on the eastern slope and inside a dead forest (FIG. 7). This find is in an area degraded by a nearby beaver plantation and eroded by rainfall events that wash sediment from a nearby stream. The most likely hypothesis is that it is an ancient hearth used in transit through the valley. It is located 15km from Roca Lake and 18km from Yendegaia Bay.

4.3 Lapataia 3

In the area of the upper course of the Lapataia River, 3 m from one of the small affluents, an alignment of stones with an empty space inside is detected (FIG. 9). The maximum length dimension is 3.70 m long and 1.70m wide, on the west side there is a short section of 0.60 m long (FIG. 8). We do not know the functionality of this structure; the hypothesis is that it is the old base of a windbreak. The site is located on the natural way up to the pass, in addition to having abundant reeds, fresh water and presence of guanaco trails.

4.4 El Paso Rock Shelter

This shelter is situated in the descent zone towards Bahía Blanca, just below the pass (FIG. 10), approximately 7.5 km from Bahía Blanca and 34 km from Bahía Yendegaia. It occupies a privileged position, offering protection from wind and rain, while providing a broad view of the valley. Flakes, a nodule and a core of a light gray siliceous material, probably quartzite, which is a raw material does not present at the site, are found throughout the shelter (FIG. 13). In total, 9 flakes are detected, 2 of which are found on the way down, which shows a percolation of the material towards the slope through the small path, transforming it into a small torrent. In addition, 2 fragments of contemporary green glass are found in the same shelter. The erosion of the small guanaco road that passes through the shelter has exposed a cultural stratum formed by ashes and coals (FIG. 11).

In the wash zone, on the way down, there is a ceramic fragment of stoneware with brown engobe (FIG. 12). It is possibly a gin bottle made between 1860 and 1940 (Henríquez Urzúa et al., 2018; Schávelzon et al., 2012). This finding is interesting, as it documents the use of the site in the early 20th century.

In the southern area of the shelter, 3 burned trees are detected, which also indicates a relatively recent use of the space, even though one of them shows considerable degradation and could be from the first half of the 20th century (FIG. 15).

4.5 Bahía Blanca 1 shell midden deposit

This shell midden deposit is in the western part of the small sub-bay in the eastern part of Bahía Blanca (FIG. 21). It is about 80 m from the coast and is protected by a rocky wall that acts as an overhang, protecting it from wind and rain (FIG. 16). In addition, it has access to fresh drinking water and the marine resources of the Bay. The main mound is in the area farthest from the wall, suggesting that the inhabitants probably resided in that dry area and dumped waste beyond the drip line.

Bone, lithic, and malacological materials are scattered throughout the occupation area. This scattering is attributed to the presence of guanacos, which utilize the site for resting and subsequently disturb the archaeological deposit. The lithic materials consist of flakes and a core made from the same greenish siliceous raw material. Regarding the bone remains, there are fragments of bird diaphyses exhibiting intentional breakage, as well as guanaco fragments displaying percussion marks (FIG. 17).

Additionally, the site is clearly impacted by a significant beaver plantation in the eastern area. This plantation has completely altered the landscape by clearing trees and flooding access to the shell midden pit. It is likely that, in the past, the shell midden deposit was situated in front of a Nothofagus forest and a freshwater stream that flowed through the center of the small sub-bay.

4.6 Bahía Blanca 2 shell midden deposit

This shell midden deposit is located on the east coast of Bahía Blanca, east of a small river mouth of glacial origin. The site is still used today by fishermen and sailors for anchoring and camping at night with views of the bottom of the Bay and the Dalla Vedova glacier.

It is located about 10 m from the shore in an open forest with a vegetation cover consisting of moss and small ferns (FIG. 18). On the edges of the river, which is about 30 m away, there are large areas covered by wild celery.

The deposit is formed by two mounds about 50 cm high by 3 m in diameter and lenga trees that have grown on top of them can be seen, as well as self-thinning (falling and lifting of the subsoil by roots) outside the shell midden area (FIG. 18). Interestingly, about 5 m from the shell midden pit there are two culturally modified Nothofagus, which could be related by dendrochronological dating and excavation of the site, since they have large bark regrowth.

4.7 Bahía Blanca 3 shell midden deposit

This shell midden deposit is lenticular and extensive (FIG. 19), not mound type like that of BB2. It is located on the east coast of Bahía Blanca, on the beaches west of a small river mouth of glacial origin. The part near the shore is eroded by the action of the tides. There is cultural material located 40 cm from the high tide line and 3 m long. In the coastal intertidal zone, there are several isolated finds of lithic tools between the BB3, BB4 and BB2 sites.

4.7 Bahía Blanca 4 shell midden deposit

This is another lenticular shell midden deposit eroded by tidal effects (FIG. 20). It is located on the east coast of Bahía Blanca, on the beaches west of a small river mouth of glacial origin. At the top is an old wooden structure that appears to have served to isolate the residents from the ground. Throughout the back forest there is evidence of the use of the forest as a sawmill with cut trees and axe marks from at least the last 50 years.

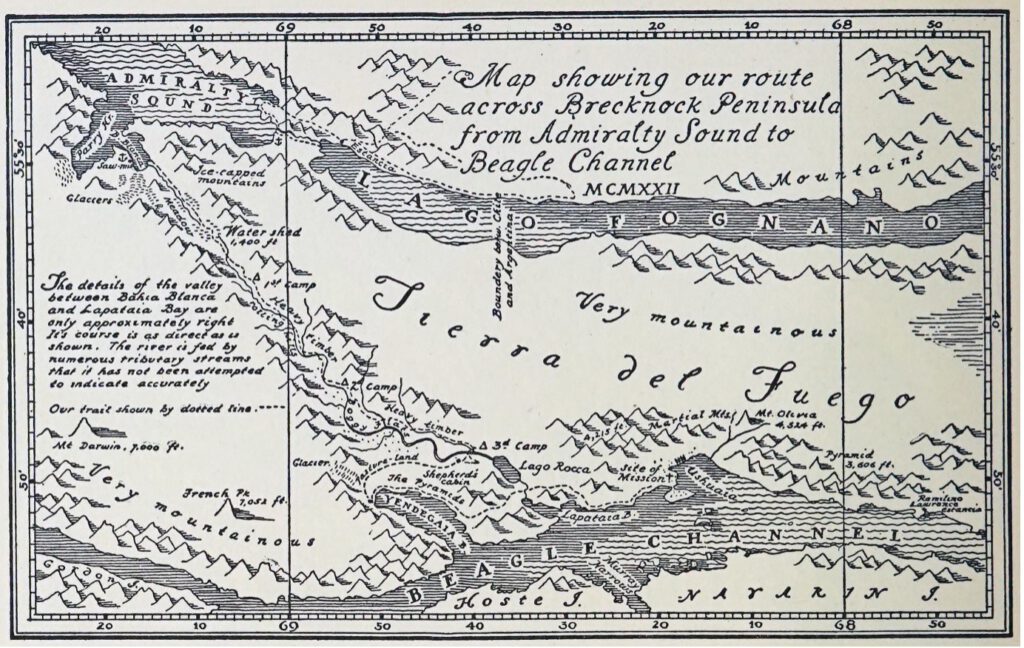

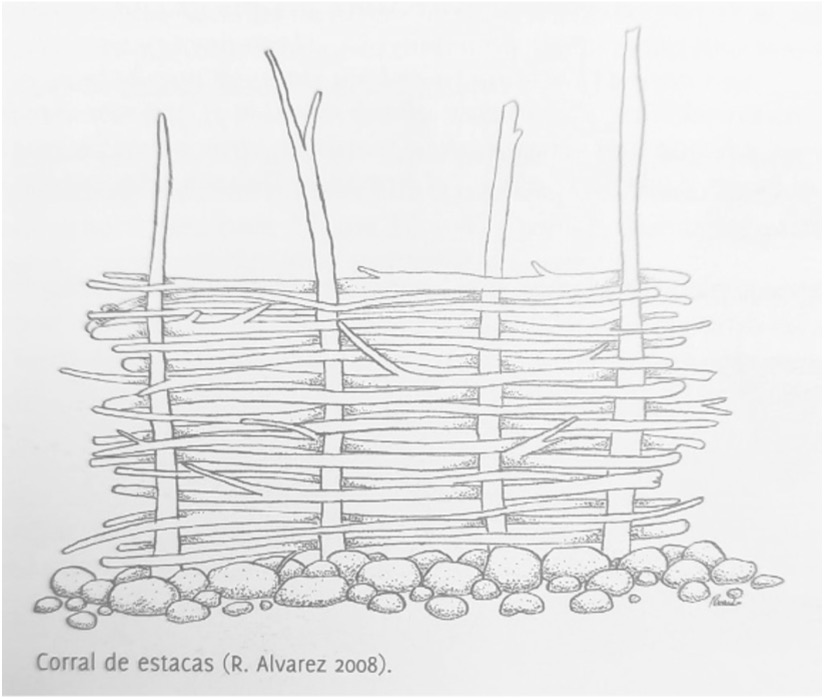

4.8 Fishing weirs in Bahía Blanca

On the south coast in the background of Bahía Blanca, Corral 1 and Corral 2 can be seen in a small sub-bay in the eastern area (FIG. 21). In the aerial photo taken with the drone it can be clearly seen that the coast is affected, as well as the location of the BB1 shell midden deposit. Corral 1 measures 70 m wide and 4400 m2, Corral 2 (more doubtful) measures 99 m wide and 6000 m2. In the case of corral 1 wooden stakes can be observed, based on this materiality, we can interpret that it is a corral of stakes or rods such as those found in Chiloé (Álvarez et al., 2008). In this case it would be late corrals from when the Chilotes began to arrive in the region, although the exact dates of this migration and the processes of exchange and use of such structures are unknown for the moment (Aguilera Águila et al., 2021; Álvarez et al., 2008). Other fishing weirs have already been identified in the northern area of Tierra del Fuego, such as in the town of Cameron, in Bahía Inútil, where a 70 m long U-shaped fishing weirs has been found (Torres, 2009). Perhaps these findings, relatively close in territory and characteristics, could be related to the same event or tradition, but we need dating to prove it.

4.9 La Paciencia Bay Fishing weirs

This wooden rod fishing weir is in what is now Bahía la Paciencia. It is in a bay with a large area of shallow delta, as is the case in Bahía Blanca. The accumulated sediment comes from the valley and is dragged by the water of the Despreciado and Deseado lakes.

© Thierry Doupradou

5.Isolated Finds

In the area of Bahía Blanca, where the BB2, BB3, and BB4 sites are located, there is a wide beach formed by the mouth of a glacial river. This beach has abundant raw material that can be used for lithic carving. In this context and considering the presence of shell middens in the vicinity, a set of 4 lithic artifacts with relevant characteristics were found. The morphological features, some of the findings, and the location in a forest used by sawmills, where the trees grow tall and straight, suggest that they could have been used as axes and discarded in the intertidal zone. The case of lithic artifact 2, perhaps the one that brings us closest to this hypothesis, as chippings resulting from use can be observed.

- Lithic 1: Igneous rock with pointed bifacial carving. Possible use as an axe.

- Lithic 2: Green siliceous rock, rounded pebble with monofacial carving and chipping from use. Possible use as an axe.

- Lithic 3: Quartzite-like siliceous rock with peripheral size reduction on a percussion plane.

- Lithic 4: Quartzite-like siliceous rock, rounded pebble with monofacial carving. Possible use as an axe.

6. Cultural marks on trees

Bark peeling marks represent a form of cultural expression observed in trees that have undergone bark removal during productive processes. These bark peelings have left their marks in various locations along the channels, providing evidence of ancestral use of the territory and sustainable management of plant resources by southern peoples over several centuries. In southern Patagonia, there are studies that have documented such evidence (see Östlund et al., 2020; Zegers et al., 2020). These types of cultural modifications in trees are usually found in places and bays protected from the wind, where trees of the kinds Nothofagus (Coihue), Drimys winteri (Canelo) and Pseudopanax laetevirens (Sauco del Diablo) grow straight.

Despite the possible detection of these marks during field investigations, there are unique challenges associated with their analysis. It is common for trees to have suffered damage not attributable to human activity, such as windthrow, fire, and branch breakage. In addition, much of the coastline, such as the Bahía Blanca basin, has been affected by sawmills and sporadic occupations by fishermen, a fact that hinders their conservation and leaves other marks that can also be easily confused.

6.1 Bahía Blanca

In this exploration, evidence of culturally modified trees has been found in the Bahía Blanca area. This bay, and specifically the forest near the Bahía Blanca 2, 3 and 4 shell middens, presents an optimal location for bark extraction. The main problem at this location is that the forest has been exploited for decades for timber extraction. Therefore, without dendrochronological dating we cannot be certain of their age and, consequently, we cannot relate them to the indigenous occupation of the site.

The first two marks close to the Bahía Blanca 2 shell midden seem to be the oldest, as well as being located a few meters away from the shell middens find. The first mark, CMT.1 (FIG. 30), measures 125 cm long by 10 cm wide, with a tree diameter of 90 cm. It has a tool mark of 8.5 cm (FIG. 32). The second mark, CMT.2 (FIG. 31), is located inside a small hole in the bark of a tree that is 75 cm in diameter. The small hole measures 7 x 5 cm and impacts from some type of tool can be observed inside (FIG. 33).

The other cases are found on the other bank of the glacial river, where late exploitation of the forest is evident (FIG. 37). The third case, CMT.3 (FIG. 34), presents a mark of 24 x 11 cm with a diameter of 51 cm, as do the marks CMT.4 (FIG. 35) (8 x 71 cm and a tree diameter of 48 cm) and CMT.5 (FIG. 36) (13 x 50 cm and a tree diameter of 38 cm).

7. Discussion

During the trip, the group searched without results in the supposed area of the camp where Rockwell Kent had spent the night and, in the area, where Kent could see the indigenous constructions. Both places are open forests with large Nothofagus and freshwater streams in the immediate vicinity. In both cases only a few trees with signs of burning could be documented, but no other archaeological material could be documented. Systematic drilling or the opening of archaeological units would be necessary to discover and ensure that these sites were occupied. Likewise, the low areas near the river, sometimes the most suitable, are completely flooded by beaver plantations that may have affected our view of other sites in the pass.

Possible place of indigenous huts documented by Rockwell Kent

GPS: -69.012617, -54.640792.

Possible Rockwell Kent Camp

GPS: -69.015727, -54.637307.

8. Conclusions

The first point, perhaps one of the most relevant, is that the landscape has been altered by the presence of allochthonous animals, which have modified the state of the terrain compared to how it would have been when it was inhabited by the indigenous communities. In the lower zone of the Lapataia Valley there are wild horses, as well as multiple beaver plantations, which have transformed the landscape. The beaver plantations are very powerful modifying agents of the landscape, since they destroy the forest and change the water courses, flooding possible roads and archaeological sites.

The crossing of the valley took a total of five days, but with more luggage and care than in the past. In addition, the fastest way, in wet conditions by the river or its edge, was systematically avoided, only using it on rare occasions. On the other hand, as we have mentioned, much of the forest, especially in the lower Bahía Blanca area and in the intermediate and lower Lapataia River area, is affected by beaver plantations, which have modified the original routes and considerably delay traffic.

In general, the archaeological landscape reveals the utilization of the pass, as well as the two bays that function as both a starting point and an endpoint. The gaps in the map are starting to be filled, and we can observe transient sites in the interior and shell remains in both bays.

However, as we have pointed out, this is a visual and not a systematic survey, so more findings could be found if a campaign dedicated to the collection of archaeological information is carried out. Significantly, this set of findings in the interior zone brings us closer and closer to a new vision of the occupation and use of the territory. These transit areas must have functioned as a nexus where an exchange, both material and of ideas, could have taken place. Perhaps an appropriate analogy is to see the transdisciplinary expedition as a new exchange of ideas; also occupying the area in a transitory way, creating new relationships, and leaving a trace in the territory.

On the other hand, the project has achieved one of its main objectives, which is to be able to make archaeological finds, but based on a transdisciplinary group with different concerns and interests. This was one of the main motivations: to combine knowledge, share it and use it to learn about the territory from different perspectives.

9.Bibliography

Aguilera Águila, N., García Piquer, A., García Pérez, C., & Piqué Huerta, R. (2021). Čelkok’enar, aproximación a la navegación indígena en Fuego-Patagonia. Revista Española de Antropología Americana, 51, 137-153. doi: 10.5209/reaa.71110

Álvarez, R., Munita, D., Fredes, J., & Mera, R. (2008). Corrales de pesca en Chiloé. Valdivia: Imprenta América.

Bird, J. (1938). Antiquity and Migrations of the Early Inhabitants of Patagonia. Geographical Review, 28(2), 250-275. doi: 10.2307/210474

Emperaire, J. (1963). Los Nómades del Mar. Valdivia: Serindígena.

Gallardo, F., Cabello, G., Sepúlveda, M., Ballester, B., Fiore, D., & Prieto, A. (2022). Yendegaia Rockshelter, the First Rock Art Site on Tierra del Fuego Island and Social Interaction in Southern Patagonia (South America). Latin American Antiquity, 1-18. doi: 10.1017/laq.2022.47

García O., S. (2015). Los orígenes de las comunicaciones terrestres en el sur de Tierra del Fuego (Chile). Magallania (Punta Arenas), 43(2), 5-45. doi: 10.4067/s0718-22442015000200001

Henríquez Urzúa, M., Lazzari Pino, G., & Díaz González, P. (2018). Las Botellas de gres de Coínco. Santiago de Chile: Andros Impresores.

Heusser, C. J., & Rabassa, J. (1988). Cold climatic episode of Younger Dryas age in Tierra del Fuego. Nature, 328(6131), 609-611. doi: 10.1038/328609a0

Heusser, Calvin J. (2003). Ice age southern Andes: a chronicle of palaeoecological events. New York: Elsevier.

Kent, R. (1924). Voyaging southward from the Strait of Magellan. New York: Halcyon House.

King, P. P. (1839). Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle (Vol.1). Proceedings of the first expedition, 1826-1830, under the command of captain P. Parker King. London: Henry Colburn, Great Marlborough Street.

Laming-Emperaire, A., Lavallée, D., & Humbert, R. (1972). Le Site de Marazzi en Terre de Feu. Objets et Mondes, 12(2), 225-244.

Legoupil, D., & Fontugne, M. (1997). El Poblamiento Marítimo en los Archipiélagos de Patagonia: Núcleos Antiguos y Dispersión Reciente. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia, Serie Ciencias Humanas, 25, 75-87.

McCulloch, R. D., Bentley, M. J., Tipping, R. M., & Clapperton, C. M. (2005). Evidence for late-glacial ice dammed lakes in the central Strait of Magellan and Bahía Inútil, southernmost South America. Geografiska Annaler, Series A: Physical Geography, 87(2), 335-362. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3676.2005.00262.x

McCulloch, R., & Morello, F. (2009). Evidencia glacial y paleoecológica de ambientes tardiglaciales y del Holoceno temprano. Implicaciones para el poblamiento temprano de Tierra del Fuego. Arqueología de Patagonia: una mirada desde el ultimo confin, April 2016, 119-136.

Milek, K. (2018). Transdisciplinary Archaeology and the Future of Archaeological Practice: Citizen Science, Portable Science, Ethical Science. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 51(1-2), 36-47. doi: 10.1080/00293652.2018.1552312

Morello, F., Contreras, L., San Román, M., & Morello Repetto, F. (1999). La localidad de Marazzi y el sitio arqueológico Marazzi I, una re-evaluación. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia, Serie Ciencias Humanas, 27, 183-197.

Orquera, L. A., & Piana, E. L. (2009). Sea nomads of the beagle channel in southernmost South America: Over six thousand years of coastal adaptation and stability. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 4(1), 61-81. doi: 10.1080/15564890902789882

Ortiz-Troncoso, O. R. (1978). Nuevas dataciones radiocarbonicas para Chile Austral. Boletin. Museo Arqueologico., 16, 244-250.

Östlund, L., Zegers, G., Cáceres Murrie, B., Fernández, M., Carracedo-Recasens, R., Josefsson, T., Prieto, A., & Roturier, S. (2020). Culturally modified trees and forest structure at a Kawésqar ancient settlement at Río Batchelor, western Patagonia. Human Ecology, 48(5), 585-597. doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00200-1

Piana, E. L., Vila-Mitjà, A., Orquera, L. A., & Estévez, J. (1992). Chronicles of ‘Ona-Ashaga’: archaeology in the Beagle Channel (Tierra del Fuego–Argentina). Antiquity, 66(252), 771-783.

Piana, E., Zangrando, F., & Orquera, L. A. (2012). Early Occupations in Tierra del Fuego and the Evidence from Layer S at the Imiwaia I Site (Beagle Channel, Argentina). Southbound. Late Plesitocene Peopeling of latin America, January, 171-175.

Ponce, J. F., Borrometi, A. M., & Rabassa, J. O. (2011). Evolución del paisaje y de la vegetación durante el cenozoico tardío en el extremo sureste del archipiélago fueguino y canal Beagle. En A. F. Zangrando, M. Vázquez, & A. Tessone (Eds.), Los cazadores-recolectores del extremo oriental fueguino Arqueología de Península Mitre e Isla de los Estados (Número May 2014). Buenos Aires: Sociedad Argentina de Antropología.

Prieto, A., Morano, S., García-Piquer, A., Navarrete, V., & Dupradou, T. (2022). Actualización del Catastro Georreferenciado de Sitios Arqueológicos de Magallanes. Tercera etapa. Informe de circulación interna. Punta Arenas: Oficina de Asuntos Indígenas de Punta Arenas.

Prieto, Alfredo, Chevallay, D., & Ovando, D. (2000). Los pasos de indios en Patagonia Austral. Desde el país de los gigantes. Perspectivas arqueológicas en Patagonia, 87-94.

Rabassa, J., Coronato, A., Bujalesky, G., Salemme, M., Roig, C., Meglioli, A., Heusser, C., Gordillo, S., Roig, F., Borromei, A., & Quattrocchio, M. (2000). Quaternary of Tierra del Fuego, southernmost South America: An updated review. Quaternary International, 67–71, 217-240. doi: 10.1016/s1040-6182(00)00046-x

Saldanha da Gama, L. F. de. (1887). Notas de viagem pelo Capitáo de Fragata Luiz Felippe de Saldanha da Gama. Annales de l’Observatoire Imperial de Rio de Janeiro, 3, 3-308.

Salemme, M. C., & Santiago, F. C. (2017). Qué Sabemos y Qué No De La Presencia Humana Durante El Holoceno Medio en La Estepa Fueguina. En M. Vázquez, D. Elkin, & J. Oría (Eds.), Patrimonio a orillas del mar: arqueología del litoral atlántico de Tierra del Fuego (pp. 75-86). Ushuaia: Editorial Cultural Tierra del Fuego.

SAMS (Ed.). (1886). The South American Missionary Magazine: Vol. XX. London: Seeley, Jackson, and Halliday, Essex Street.

Schávelzon, D., Frazzi, P., Carminati, M., & Camino Ulises, A. (2012). Borrachos en la patagonia: clasificando envases de gres y sus problemas. Arqueología Histórica en América Latina. Perspectivas desde Argentina y Cuba. Buenos Aires (Argentina): Programa de Arqueología y Estudios Pluridisciplinarios, 87-98.

Smith, M. L. (2014). Citizen Science in Archaeology. American Antiquity, 79(4), 749-762. doi: 10.7183/0002-7316.79.4.749

Torres, J. (2009). La pesca entre los cazadores recolectores terrestres de la isla grande de tierra del fuego, desde la prehistoria a tiempos etnográficos. Magallania, 37(2), 109-138. doi: 10.4067/S0718-22442009000200007

Zangrando, F. (2009). Historia evolutiva y subsistencia de cazadores-recolectores marítimos de Tierra del Fuego. Buenos Aires: Sociedad Argentina de Antropología.

Zegers, G., Fernández, M., Cáceres, B., Prieto, A., Carracedo, R., & Östlund, L. (2020). Reporte del hallazgo de árboles culturalmente modificados en bosques costeros de Nothofagus Betuloides (Mirb.) Oerst 1871 (Nothofagaceae) por pueblos canoeros de la Patagonia austral y Tierra del Fuego. Antropologías del Sur, 7(13), 245-253. doi: 10.25074/rantros.v7i13.1726

(joint work by Dr. Robert Carracedo Recasens, Dr. Alfredo Prieto)

[1] The metres above sea level correspond to the level of the sea. The shells are much closer to the high tide line, between 1 and 3m.

[2] Years before present, equivalent to 1950, the standard year for Carbon 14 dating.

[3] The expedition led by frigate lieutenant Tomás Zurueta in 1892 had already passed along the route between Lapataia and Bahía Blanca (see García O. 2015).

[4] The order of the findings presented below is based on the route taken.