The origin of this work dates back to 2015, following a visit to the Gusinde-Hagenbeck collection consisting of cultural objects originally belonging to the Kawesqar, Selk’nam, Yagán and and Aonikenk peoples, which are now housed in the Weltmuseum, Vienna (formerly the anthropological museum).

The review of this collection was initially conducted by Alfredo Prieto and Nicolás Spencer in collaboration with the curator of the South American collection, Claudia Augustat. This study aimed to achieve a more precise understanding of the objects and their anthropological value due to the different ways they were obtained; Gusinde acquired the objects through questionable anthropological purchase processes, while Hagenbeck obtained these cultural elements as “adornments” of people who were exhibited in human zoos.

Additionally, this review was oriented towards understanding the factors that give an object its value. In other words, what human and non-human operations transform an everyday artifact into one with museological status. These questions motivated extensive field research in museums and the territory, scientific support, and above all, experimentation through artistic tools.

From our first meeting with Claudia and Alfredo arose the idea, or rather the hypothetical proposition, of repatriating the objects. A process that, given governmental, technical, and socio-cultural difficulties, we knew was impossible to accomplish. Nonetheless, we deemed it important to review and analyze the complexities surrounding both the objects and the people, institutions, and spaces that should be involved in such a process. This was done with the understanding that we have no sense of ownership over these objects, recognizing that any real action must be undertaken by those who legitimately believe they belong to them, and knowing that relocating them is as difficult, if not more so, than their expatriation.

Gusinde-Hagenbeck Collection

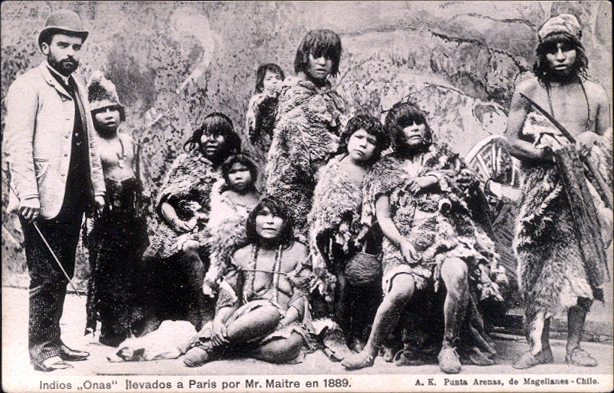

Carl Hagenbeck was a German zoologist, animal trainer, and circus director, born in Hamburg in 1844. A member of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory, he was a significant precursor of anthropozoological exhibitions and the founder of the Tierpark Hagenbeck zoo in 1907.

Hagenbeck traded in the living bodies of the inhabitants of Patagonia for display in a modern zoo, which was, apparently, permeated by the ideals of conservation and appreciation of nature brought by modernity. Analyzing the contents of zoos, as well as museums and world fairs of that time, makes it evident that the ultimate goal was to exalt European powers by emphasizing the distance between barbarism and modernity.

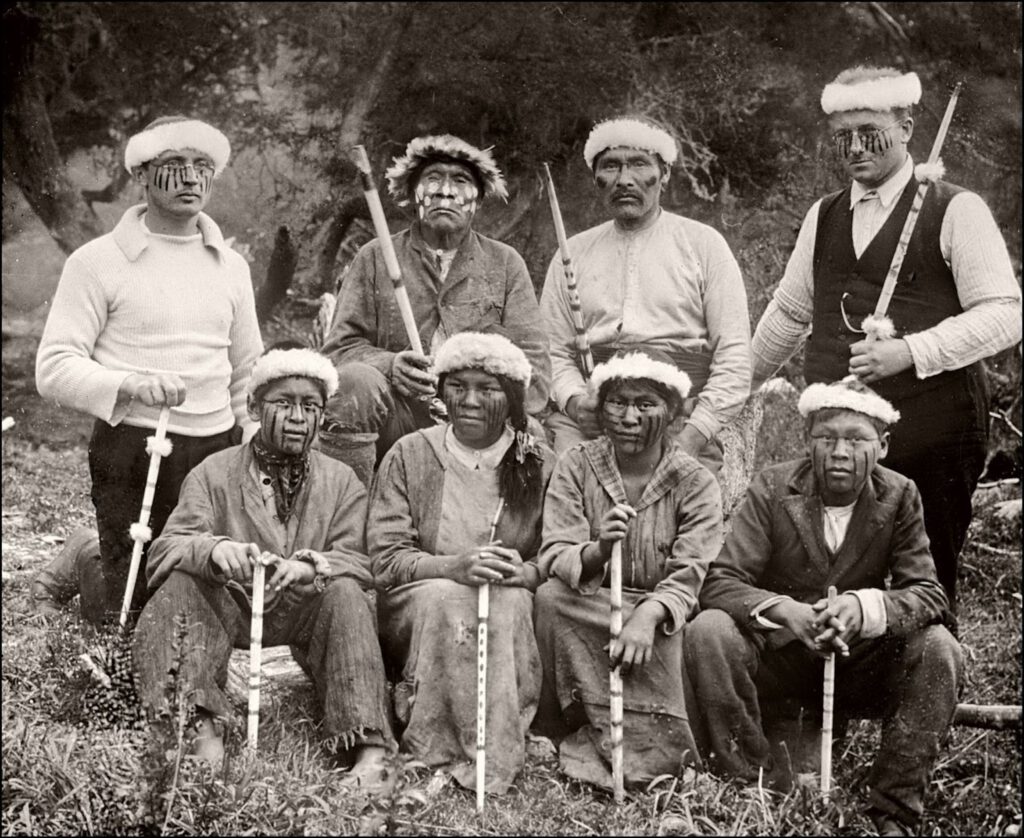

Paradoxically, the objects obtained from the Fuegians who were kidnapped and exhibited in human zoos contain great anthropological value despite their deplorable method of acquisition. Their value lies in their actual everyday use. This is in contrast to objects obtained by commercial ships, which took advantage of their journeys to buy rarities and thus increase their coffers from the extraction of resources such as gold, meat, wool, fat, wood, and furs. Thus, the objects sold were simulated and adapted for trade. Among the indigenous people, however, real personal items were normally carefully transported by their owners, destroyed, or buried with them upon their death.

Martin Gusinde, an Austrian missionary and ethnologist, dedicated much of his life to studying the inhabitants of Patagonia, describing, among other things, the devastating impact that colonization and economic exploitation had on these peoples. His vast work extensively describes the objects obtained in his four expeditions between 1918 and 1924.

As a member of the religious order of the Missionaries of the Divine Word and a disciple of the Catholic priest, linguist, and ethnologist Wilhelm Schmidt, he oriented his reflections and conclusions towards the verification of the theory of primitive monotheism. This line of thought was based on the belief that primitive religion, that is, of almost all tribal peoples, began with an essentially monotheistic concept. The pressure to verify this theory, along with the brevity of his travels (although numerous), forced the exchange of animals, tobacco, or clothing to obtain objects and information from classified traditions and rites. This was the case with the Hain initiation ceremony, which he was able to document after paying 360 lambs.

The advance of civilization revealed the secret of the lodge, so jealously guarded by countless generations. Women learned of the deception, and the Indians were induced, with some money, to perform comedies before audiences of scientists. I have seen photographs in which the actors appear with short hair and painted as they never were in my time (Lucas Bridges, 1952; 438-39).

Analyzing the Gusinde collection, one observes masks of a size that does not correspond to that of adults for whom these masks are intended in secret ritual ceremonies. Their size seems to be an adaptation from the sacred rite to the exchange rite, where the anxiety of the collector and the need of the provider, in this case, a product, prevail. For this reason, the Gusinde collection should be observed carefully, without demeaning it but analyzing it in its proper context.

Considering the motivations, origin, and context of these two collections, their components should be thought of as objects with their own agency and dynamism. Everyday artifacts capable of transforming into museum pieces that represent distant customs, to then mutate into the mirror of the society that contains them in its museum. A basket, a toy, a harpoon, or a ritual mask are rather meta-anthropological objects that describe or explain the methodologies and the agenda underlying their collectors.

Repatriation

The idea of “repatriation” is surrounded by debatable issues, such as the concepts of homeland/patria1, origin, ownership, belonging, and technical possibilities of conservation, etc. Taking this into account, we initially deliberated the hypothetical possibility of relocating the objects to a local museum or one near the place where they were obtained. This was discarded as we thought that repatriating cultural objects from one museum to another is more of a spatial transfer but symbolically static. On the other hand, the idea of transporting them to the original communities seemed to us more than a theoretical and symbolic discussion; it was a political issue we could not be part of.

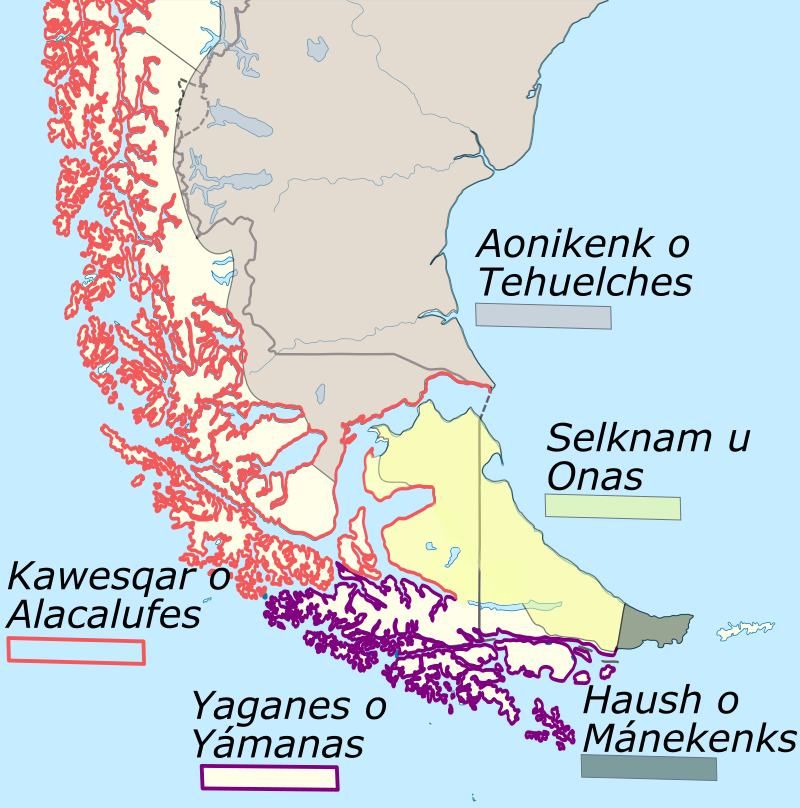

Thus, the idea of repatriation to the territory arose, to the place—and not necessarily the people—from where they were extracted. What place in Fuego Patagonia could have the suitable characteristics to house this collection? Three indigenous peoples are implicated in these collections: Yagán, Kawesqar, and Selk’nam. We believed that a meeting point between them could be an ideal location for their relocation.

Analyzing maps of the distribution of indigenous peoples, we found a common point among these three cultures. This point was in the southwestern mountainous and archipelagic zone of Tierra del Fuego, at latitude 54°. This is where the Yendegaia National Park is currently located, in the valley that traverses the Darwin Mountain Range, between Bahía Blanca and Bahía Yendegaia, connecting the Admiralty Sound with the Onashaga Channel (Beagle).

Some authors already noted accounts indicating a possible passage between the Beagle Channel (Yagán territory) and the Admiralty Sound (Kawesqar territory) through a nearly 40 km long passage across Selk’nam territory. As R. Carracedo and A. Prieto indicate in their report: “The different explorers who started their search and crossing, like Otto Nordensjköld (1896), Carl Skottsberg (1908), or Alberto de Agostini (1913), were already aware of previous information that an ‘aboriginal’ passage existed. In fact, Thomas Bridges in 1885 had already noted the use of the passage by the communities arriving at the Ushuaia Mission (SAMS, 1886).”

With this information, we proposed that a passage could be suitable for a museum of “nomadic objects”. This proposal raised other questions: Does the category of a museum apply? What characteristics should a space have to preserve cultural objects that are currently in climate-controlled chambers? Is their conservation important? For whom? What makes the hyper/objects present there, such as rivers, mountains, winds, and tectonic layers, not have the same cultural museographic value? Does the condition or value of a natural space change by containing cultural objects?

These are some of the questions that led Terra Ignota to carry out its expedition to this area and to involve the community in the discussion. A physical and theoretical place that we would call the Intercultural Contact Zone (ZCI).

1 This concept has its roots in the Spanish word ‘patria’ or ‘land of the fathers,’ a concept rooted in a physical space, territory, people, region, country, or nation, and has been used to justify nationalist policies, ethnic or territorial exclusions, and internal or international conflicts.