Before the research trip to the Zona de Contacto Intercultural, Fernanda Olivares and Nicolás Spencer were invited to participate in a residency at Weltmuseum Wien to be part of the exhibition “Extinction!?” as part of the TAKING CARE project. The idea of this residency was to work with objects from the collections obtained by Martin Gusinde and Carl Hagenbeck and explore new museographic approaches based on perception, feelings, the discussion around extinction, and the recognition of the Selk’nam community in Chile as a living community.

We investigate the objects of the Selk’nam collection to later display the results for a year in the exhibition rooms of this former anthropological museum. We approached these objects cautiously, understanding that they have their own position and agency independent of who observes them, a place as a result of a long history, with multiple meanings and ways of being interpreted. For this, we began by understanding their ecosystem, from the periphery of the city to the elemental particles that constitute these artifacts.

We initiated a field study that began in the city of Vienna, exploring its cultural environment through its museums and their different logics of representation. In pursuit of this goal, we interviewed people connected with various museums and institutions such as the Weltmuseum, Vienna (Claudia Augustat, Christiane Jordan), the Museum of Natural History (Constanze Schattke), the Missionshaus St. Gabriel (Fr. Franz Helm), and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Mumok (Susanne Neuburger).

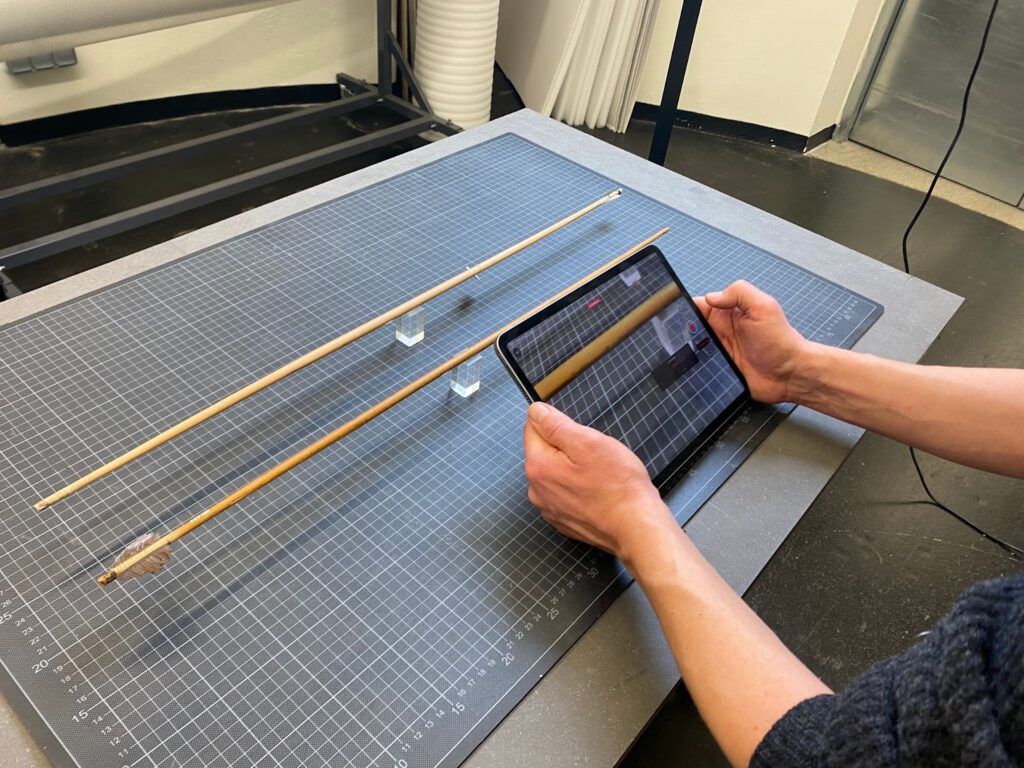

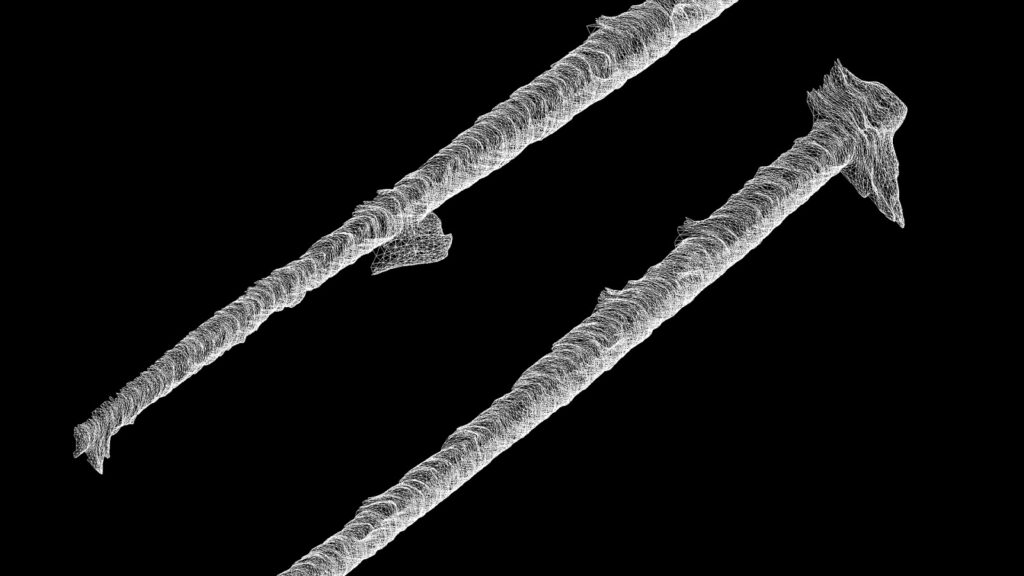

Then we delved a little deeper, cautiously observing the isolated objects in the display cases of the exhibition hall, moving through restoration laboratories to the storage and conservation warehouses. We transitioned from the controlled atmosphere that preserves them to using scanning and 3D modelling technologies to simulate the surface that is in constant contact with it.

Thus, from the original object, we created a vectorial and empty form, whose interior would need to be filled through creative heritage practices or what we would call “lies.”

For some, lying is an immoral act; for others, it is an act of survival.

Many of the objects in the Gusinde-Hagenbeck collection were taken violently from their users. This, combined with the systematic attempt to annihilate their owners, caused these artifacts to arrive at the museum with little or no information. The same happened with their descendants, including Fernanda Olivares, who has been in a process of reconstructing her past for years. To do this, Weltmuseum Wien allowed her to come into contact with the objects, touch them, smell them, and ask them about their past. In this way, Fernanda reconstructed part of her heritage through a story she created. A version that does not contradict but rather adds to what is catalogued by 19th-century anthropologists and interpreted by thousands of museum visitors. We are based on the idea that imagination is just another portrait of reality, that it cannot go as far as believed, and that the most delusional idea is just another colourful portrait from the palette of what can be considered reality.

Video

The video is an essay, as mentioned, about museum ecosystems and the objects originally belonging to the Selk’nam community. The objects were scanned and emptied of their content, making them transparent so that later, through a creative process, Fernanda Olivares could re-signify them through a story, a narrative about their utility or meaning. Additionally, we integrated the sounds that coexist with these objects in the rooms that house them, along with their visitors and the people who care for and exhibit them.

After our trip to the Intercultural Contact Zone, we added footage from the places we visited in the field to the video, starting at minute 15:45. These places were similarly scanned and vectorized, to be emptied and re-signified with a perspective that invites natural spaces into the museographic discussion; the “natural” ecosystems become cultural as they are inhabited by humans, giving rise to future archaeologies.

Repatriation practices

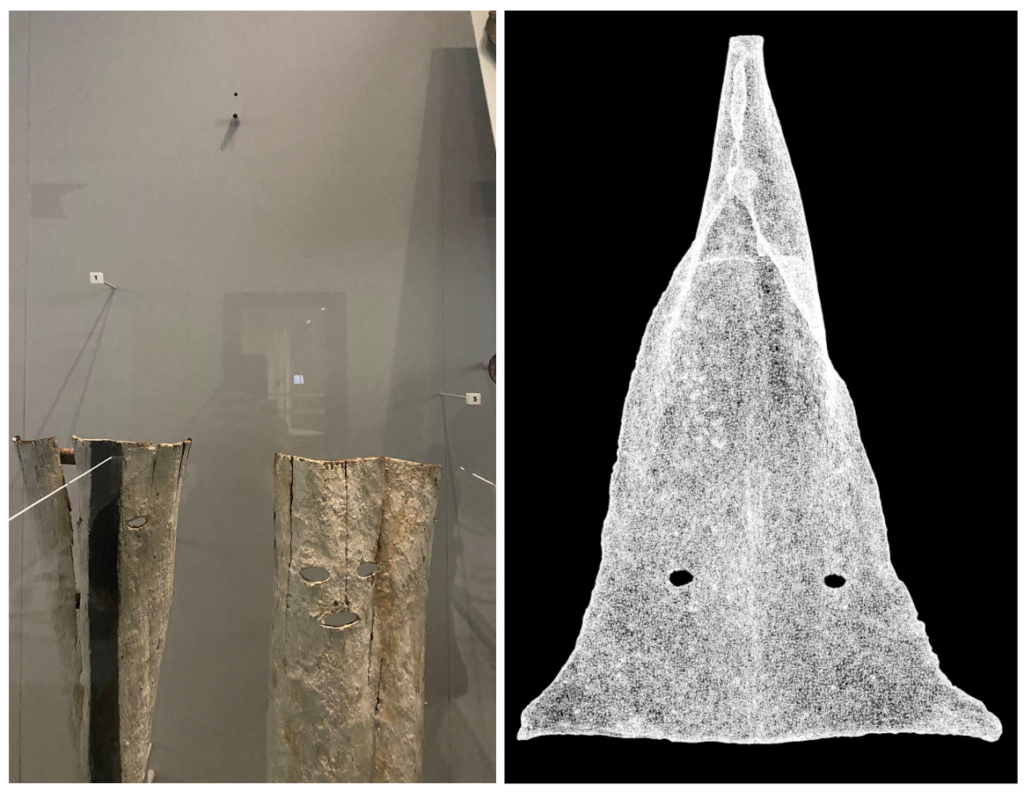

The ceremonial mask featured in the video (at 5:00 minutes) was removed from the exhibition at the request of Fernanda Olivares. After being scanned, it was printed in two copies: one remained in the ‘Extinction!?’ exhibition at the Weltmuseum Vienna, and the other was taken back to Tierra del Fuego by Claudia Augustat, curator of the South American collection at that museum. Although the plastic replica’s transfer did not adhere to any repatriation protocols, it allowed us to engage in a symbolic exercise, gaining insight into the mechanisms at play and attributing value and meaning to an object with a clear origin but imprecise significance. After its return journey, the mask would be handed over to two representatives of the Selk’nam Hach Saye Selk’nam foundation: Hema’ny Molina and Fernanda Olivares.

Once in Tierra del Fuego, we were invited to a ceremony at Parque Karukinka. There, the mask protection was removed, and it was symbolically presented to the forests from where it was originally taken over 100 years ago by German missionary Martín Gusinde. During this event, the plastic replica was anointed with animal fat using traditional colors that were historically used to paint bodies and cultural objects. This gesture transformed an inorganic material into a living symbol, turning an empty form into a symbolic container of repatriation.

We were aware that the plastic mask could be seen as an extracted and exoticized object. Nevertheless, for those of us participating in the ceremony, the focus shifted away from the object itself and toward the gesture. This reversal turned a materialistic exercise into a ‘total social fact1,’ where the mask’s importance was no longer about the wearer but rather the projection of their gaze into the forest. It leads us to consider that perhaps the essence of repatriation or re-signification lies in the practice itself, and the separation of subject or object from their environment is the root of colonization, modernity, and disarray

Dislocations / Extinction!? installation

The installation was set up in “The Corridor of Astonishment” (Der Korridor des Staunens) at the Weltmuseum Wien between February 23, 2023, and April 2, 2024. The concept was to position the video in a way that creates a dislocation between the viewer and the location of the exhibited objects in the museum.

The video, which creatively explains the meaning or use of “cultural objects,” can be viewed while sitting on a plinth inside a display case. Simultaneously, a copy of the Selk’nam ritual mask, which was removed from the exhibition, observes from outside as visitors to the “Extinction!?” exhibit learn from the video. What is exhibited is the visitor’s attempt to understand a collection through imaginative exercises.

The mask leaves the display case and observes the same situation it was in for years, while the other copy is in Tierra del Fuego, observing the valleys, forests, and bays from where it was once taken. Meanwhile, the original mask returns to the storage room, where it is preserved in a climate-controlled and dark chamber.

“It was important for this piece to exchange positions between observer and observed, placing the viewer as an object of study. The museum visitor trying to understand other cultures is an anthropological phenomenon that can be exhibited and studied.” Fernanda Olivares

Contact Zone; A Park? A Museum?

One of the goals of our field study in Tierra del Fuego was to identify and validate a contact zone between the Kawésqar, Yagán, and Selk’nam cultures—an area with natural and cultural qualities that could house contemporary museological collections. The idea was to come together to dialogue and try to understand the spaces that could represent parks and reserves aimed at conservation, museums as effective places of care, and potential spaces of cultural representation.

Parks, Reserves, and Sanctuaries

In Chile, the designations of National Park, National Reserve, and Nature Sanctuary supposedly offer guarantees for the comprehensive care of unique ecosystems. However, in reality, their protection extends only as far as the interests of private entities and state policies allow.

According to Paula Urdangarín, “Analyzing the current protection figures, we can conclude that there is no absolute protection for these areas in our legislation. Legal gaps can—and are—exploited to allow economic interests to prevail over the real safeguarding of these zones. There is legal ambiguity regarding supposedly protected areas, and no long-term certainty exists”. See http://terra-ignota.net/2023/07/03/environment-as-a-legal-entity/

Parks in Chile do not include coastal borders nor the communities that have interacted with these areas for thousands of years. Their geographical limits, in addition to lacking strong ecosystem considerations, form a political imaginary that changes over time and is responsible for why today their ancestral inhabitants cannot walk or navigate freely. On the other hand, we believe it is important to establish transnational norms for ecosystem protection that transcend geopolitical divisions.

In some parks protected by private entities, non-governmental organizations with significant economic interests are involved. This suggests apparent care strategies for future, more profitable resource extraction. Therefore, solid legislation is needed to ensure the care of these ecosystems independently of the will or interest of the private organizations that guard them.

Regarding this topic, the idea arises to seek new legal figures that protect rivers, mountains, and lakes as entities with rights to shield them from transient political and economic interests. It is essential to unify international criteria and globalize experiences such as granting rights to Pachamama (Ecuador, 2008); the Law of Mother Earth’s Rights (Bolivia, 2010); assigning legal personhood to the Atrato River (Colombia, 2016); granting legal personality to the Whanganui River (New Zealand, 2017); and granting legal personality to the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers (India, 2017). These approaches are based on the idea that effective environmental protection requires recognizing its intrinsic value and ensuring its legal defense by granting rights with regulations that generate reciprocal relationships in the long term.

Terra Ignota Forum: Some Considerations

After a 10-day expedition and finding evidence of an Intercultural Contact Zone in Yendegaia Park, we debated for three days about the qualities of this park as an area with natural and cultural characteristics that could house contemporary museological collections. The debate, called the Terra Ignota Forum, involved the local community, park rangers, scientists, artists, philosophers, and curators.

As a result of this encounter, it seemed to us that the idea of a park as a museum, at least in Chile, does not guarantee the protection of the contents housed within it. An ontological shift of this nature, while an interesting starting point for reflection, would only be a semantic exercise. On the other hand, we believe that museums in general have lost representativeness, as society does not identify with them, their contents, or the necessary narrative that makes them possible.

Here, it is interesting to think in reverse; the museum as a park. The idea of the landscape as a space for contemplation and reflection seems to have shifted to museums and cultural institutions through the passive and unidirectional relationship they have with their visitors. Instead, one could think of a museum-park as a ‘place where the arts are cultivated,’ an open space for experimentation, play, and speculation where the visitor engages with poets, writers, or scientists in a non-hierarchical, horizontal, and democratic way. A space where the absurd division between culture and nature is dissolved to seek more relevant spaces for exchange and interaction.

1 Marcel Mauss, in his influential work “The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies” (1925), introduces the concept of the “total social fact”. This term refers to the idea that social phenomena cannot be understood in isolation but are intrinsically interconnected and form part of a broader whole.